About Davidsonville September 30, 2013

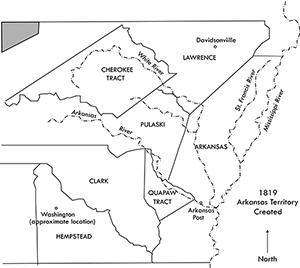

Davidsonville, Arkansas was the first county seat town in Arkansas. Platted in late 1815 or early 1816, and originally part of Missouri Territory (1815-1819), it thrived for about 15 years, when the county seat was moved to Jackson (1830), Smithville, and eventually Powhatan. Creation of the town was the work of a group of influential businessmen who wanted to break away from the territorial centers of St. Louis and Ste. Genevieve in Missouri Territory. Davidsonville was the county seat for the newly formed Lawrence County, including most of the northern one-third of present day Arkansas. It became part of Arkansas Territory in 1819. All of present day Missouri and Arkansas were acquired by the United States in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Davidsonville Historic State Park is now in Randolph County, Arkansas.

Davidsonville, Arkansas was the first county seat town in Arkansas. Platted in late 1815 or early 1816, and originally part of Missouri Territory (1815-1819), it thrived for about 15 years, when the county seat was moved to Jackson (1830), Smithville, and eventually Powhatan. Creation of the town was the work of a group of influential businessmen who wanted to break away from the territorial centers of St. Louis and Ste. Genevieve in Missouri Territory. Davidsonville was the county seat for the newly formed Lawrence County, including most of the northern one-third of present day Arkansas. It became part of Arkansas Territory in 1819. All of present day Missouri and Arkansas were acquired by the United States in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Davidsonville Historic State Park is now in Randolph County, Arkansas.

After the county seat moved from Davidsonville in 1830, the fate of its buildings is not known. It is possible that some residents remained, since the ferry across the Black River would be operational into the early twentieth century. Visitors to the town site in the late 1880s reported that some of the brick courthouse was still standing, and foundations of other structures were visible (Penn 1965).

Interest in the town was rekindled during the Arkansas centennial in 1936, eventually resulting in donation of most of the site to the state in 1957. The land was donated by Mr. and Mrs. Newt Davis and Mr. and Mrs. Eugene Sloan. The site became a state park in 1957. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969.

Interest in the town was rekindled during the Arkansas centennial in 1936, eventually resulting in donation of most of the site to the state in 1957. The land was donated by Mr. and Mrs. Newt Davis and Mr. and Mrs. Eugene Sloan. The site became a state park in 1957. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969.

Since there are no longer any nineteenth-century buildings standing at Davidsonville, it is significant as an archeological site that has the potential to provide an unprecedented view of life in an established town along the Arkansas frontier. Davidsonville retains evidence of the beginnings of the system of justice that we know today. The town was forerunner in the inauguration and spread of the national government’s bureaucratic system by virtue of its postal stop and land office. It was an important stop along the Black River and a vital ferry location. It was also a “melting pot” of cultures and ethnic groups meeting along the frontier, including French, American, African-American, and Native American peoples.

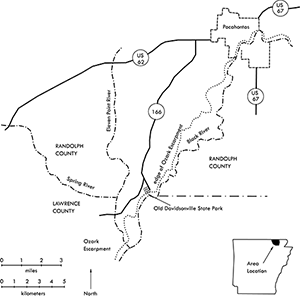

The site of the town was chosen, in part, because of its setting near the confluences of the Black, Eleven Point, and Spring rivers. This was an area rich in natural resources such as timber, wild game, and mussel shell. It was an important entry point into Arkansas for settlers coming west from Illinois, Tennessee, and places further to the east.

The site of the town was chosen, in part, because of its setting near the confluences of the Black, Eleven Point, and Spring rivers. This was an area rich in natural resources such as timber, wild game, and mussel shell. It was an important entry point into Arkansas for settlers coming west from Illinois, Tennessee, and places further to the east.

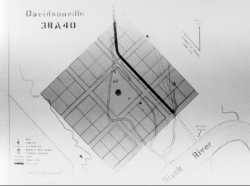

The town’s public square, including the site of the courthouse, was situated near the crest of an alluvial river terrace. The land falls gently southeasterly for about 350 yards to the banks of the Black River, about 40 feet lower than the courthouse location (Dollar 1979:22-23). Native American occupation around A.D. 1200 increased the height of the terrace by at least 20 inches (House 1980:51).

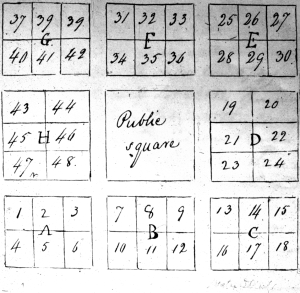

Archeological research began at Davidsonville in the 1970s, when State Parks wanted to build recreational facilities at the park. At that time a base map was made of the site, and it was superimposed over the 1815 plat map in an attempt to locate the town’s blocks and streets on the ground. In 1976, Clyde Dollar researched historical documents, focusing on the ownership history of town lots. His efforts showed that little was actually known about the site beyond speculation. He reconstructed an outline of the town’s history, beginning with several Frenchmen who settled in the area in the early 1800s. He discovered that apparently no drawings or reliable descriptions of the courthouse survive (Dollar 1979).

Archeological research began at Davidsonville in the 1970s, when State Parks wanted to build recreational facilities at the park. At that time a base map was made of the site, and it was superimposed over the 1815 plat map in an attempt to locate the town’s blocks and streets on the ground. In 1976, Clyde Dollar researched historical documents, focusing on the ownership history of town lots. His efforts showed that little was actually known about the site beyond speculation. He reconstructed an outline of the town’s history, beginning with several Frenchmen who settled in the area in the early 1800s. He discovered that apparently no drawings or reliable descriptions of the courthouse survive (Dollar 1979).

The Arkansas Archeological Survey conducted excavations at Davidsonville in 1979 and 1980 (Stewart-Abernathy 1980). In 1979 part of the courthouse foundation was uncovered, and hand-molded bricks of native clay---the remains of a chimney---were found in a low mounded area in Lot 9. This work confirmed that the courthouse was in the center of town, and that a structure was present in Lot 9. The building in Lot 9 may have faced the courthouse and was close to the northeastern edge of the lot, nearest the road. The 1980 Arkansas Archeological Survey/Society annual training program was held at Davidsonville Historic State Park. Additional portions of the courthouse foundation were unearthed, along with evidence of a structure in lots 19 and 20.

The Arkansas Archeological Survey conducted excavations at Davidsonville in 1979 and 1980 (Stewart-Abernathy 1980). In 1979 part of the courthouse foundation was uncovered, and hand-molded bricks of native clay---the remains of a chimney---were found in a low mounded area in Lot 9. This work confirmed that the courthouse was in the center of town, and that a structure was present in Lot 9. The building in Lot 9 may have faced the courthouse and was close to the northeastern edge of the lot, nearest the road. The 1980 Arkansas Archeological Survey/Society annual training program was held at Davidsonville Historic State Park. Additional portions of the courthouse foundation were unearthed, along with evidence of a structure in lots 19 and 20.

With generous funding from the Arkansas Natural and Cultural Resources Council (ANCS), and Arkansas State Parks, the Arkansas Archeological Survey conducted extensive archeological excavations and archival research at Davidsonville. Beginning in 2004, research focused on gathering additional data on the courthouse and Lot 9 structure, and the search for other buildings, including outbuildings. Archival research was conducted in order to better understand the context of the town site in its function as a county seat and a riverine trading center (Cande 2005, 2006; Cande et al. 2007, 2008, 2009).

Over the next five years, the remains of a structure were found in Lot 35, and additional artifacts were collected from lots 19 and 21. Evidence of a blacksmith shop and possible residence were also discovered in Lot 23.

The ultimate goal of this work is to support interpretation of the town site for the public. At the local level, some descendants of the original founding families of Lawrence and Randolph counties reside in the area. Many visitors to the park have similar family histories in which their ancestors settled new territories and founded new towns on the American frontier. Davidsonville is one of a few surviving territorial settlements in Arkansas.

Town Plan

The plat map of Davidsonville was made official in early 1819. The new town had been laid out and platted by surveyor James Boyd. His survey platted nine blocks of land, with the central unplatted block designated as the Public Square. Four interior streets were also laid out.

The grid pattern of town planning in America has it antecedents in England (seventeenth and eighteenth centuries) and even earlier in Greece and Rome (Stanislawski 1946). Early settlers in New England “endorsed the town as the chief, if not the only, settlement form” (Earle 1977:36). As the frontier pushed further westward, the town was seen as the most basic and conservative frontier institution. Settlement patterns in the southern colonies were also influential. In most southern colonies, and especially in Georgia, efforts were made to induce settlers to live in compact communities.

The town plan of Davidsonville may have had its antecedents in what Reps (1969) calls “isolated courthouse-square compounds” of eighteenth-century Virginia. These consisted of a courthouse, jail, caretaker’s residence, and a row of lawyer’s offices in a compound surrounded by a brick wall. A tavern or inn was nearby. Basically these towns were inhabited only when court was in session. Reps (1969:127) calls them “an expression of and a concession to the essentially rural character of the early commonwealth seats.”

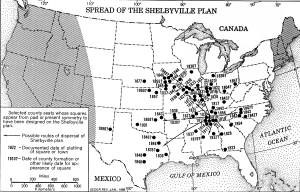

Geographer Edward Price (1968) developed a typology of central courthouse squares in America based on a survey of hundreds of town squares. He notes that there seems to have been no manuals on how to form a new county and little evidence of town planning. How did these “mental templates” for town configurations spread? One town copied another as settlers moved further west. Price defines four types of central courthouse squares: Shelbyville, Lancaster, Harrisonburg, and Four-block. Davidsonville conforms to Price’s Shelbyville square, whose prototype is Shelbyville, Tennessee, platted in 1806.

Following from the grid pattern town by the early eighteenth century was the “county-seat square,” focused on the courthouse, “emphasiz[ing] the view from edge to center” (Price 1968:31, 37).

Courthouse

Archival Evidence

Creating a 3-dimensional digital model of the courthouse at Davidsonville was a challenge. While there is archeological evidence to rely on, there is almost nothing in the written records about the building. In Davidsonville’s earliest years, court sessions were held in private homes. The county paid various residents for this service. The first mention of court being held “at the courthouse in the Town of Davidsonville” is Monday, May 13, 1822 (Allen 1995:14). Elsewhere in county records, however, a public sale “at the courthouse door” on November 4, 1818 is described (Allen 1995:33).

The courthouse is mentioned only three more times in the Lawrence County Circuit Court records. The sheriff is ordered on Saturday July 29, 1820 to “procure for the use of the county 6 chairs and a table” (Allen 1995:8). On November 9, 1825 there is the following item: “Ordered by the court that the Commissioners of the courthouse and jail do repair the windows of the court house, and repair the box and clerk’s desk so as to make them more convenient and comfortable” (Allen 1995:23). The following year mention is made that the sheriff was “Ordered…to make any repairs to the courthouse that may secure the same from injury” (Allen 1995:24).

Fortunately, there is much information on the evolution of American county seat towns, and specifically, courthouses from neighboring states. Courthouses were typically the first brick structures built in a new town. In some instances, the town commissioners advertised in the newspaper looking for a builder for the new courthouse. This happened in November 1812, in the town of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, with an announcement published in the Nashville Whig:

According to the advertised specifications, the building was to be two stories tall and forty feet square. The foundation was to be of stone, “sunk two feet under ground, and raised two feet above, the stone above ground to be neatly dressed,” its brick walls, two feet thick with ten windows below and thirteen in the second story. Interior walls were to be wainscoted “as high as the win-dow-sill, and plaistered [sic] and whitewashed above to the ceilings,” made of poplar “neatly planed and beeded [sic].” Exterior and interior doors were to be paneled, “with sufficient locks and hinges.” The roof of yellow poplar shingles was to be “nailed on with good and suitable nails” and painted red.

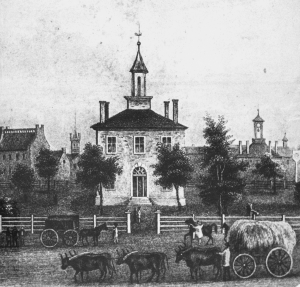

Tolbert (1999:41) recounts that other brick courthouses in the Middle Tennessee region followed this basic design. These structures stood two stories high, usually on stone foundations. Some were embellished with arched windows and doors or marbleized painting techniques on the interior. The structures were usually capped by a hipped roof with a cupola in the center. Shingles would have been painted red or brown.

As in Tennessee, early settlers in Missouri favored a county courthouse that was square or nearly square, two stories with a center entry and regularly spaced windows. The truncated hipped roof often had a cupola, frequently topped with a large ball or decorative weather vane. More than 40 such courthouses were built in Missouri between 1822 and 1885 (Ohman 1981).

Archeological Evidence

One of the goals of the Arkansas Archeological Survey’s spring 2004 excavations at Davidsonville was to relocate and gather information on the courthouse. From the 1979 and 1980 excavations, we knew that the courthouse foundation was composed of dry-laid dolomite (limestone) slabs. Brick rubble and fragments of mortar made of lime and sand were found in excavation units, along with hand-wrought lathing nails used to attach thin strips of wood to carry wall plaster. A special 8 inch by 8 inch “double brick” was unearthed atop the foundation wall. This brick may have been part of the floor inside the courthouse.

One of the goals of the Arkansas Archeological Survey’s spring 2004 excavations at Davidsonville was to relocate and gather information on the courthouse. From the 1979 and 1980 excavations, we knew that the courthouse foundation was composed of dry-laid dolomite (limestone) slabs. Brick rubble and fragments of mortar made of lime and sand were found in excavation units, along with hand-wrought lathing nails used to attach thin strips of wood to carry wall plaster. A special 8 inch by 8 inch “double brick” was unearthed atop the foundation wall. This brick may have been part of the floor inside the courthouse.

In 2004 three excavation units were opened. We found three corners of the courthouse foundation (one in each unit) in varying states of preservation. The largest and best preserved foundation element was the northeastern corner of the building . This corner is fully intact to the mortar at the base of the bricks. It also shows how the brick was laid on the first floor interior, with a row (or several rows) of single bricks (or headers) around the edge of the floor and the square “double bricks” laid inside the single bricks. Re-excavation and expansion of an excavation unit from 1979 revealed a second corner, with only the dolomite foundation remaining. This would have been the southeastern corner of the building. In the third excavation unit, only a portion of the limestone foundation remained. This evidence indicates that the first floor of the building was “on grade” instead of having a wooden floor and crawlspace.

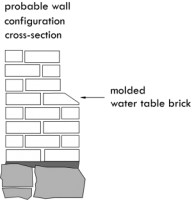

Artifacts found during the 1979, 1980 and 2004 excavations include 50 pieces of window glass, thousands whole bricks and brick bats, along with brick rubble, fragments of mortar and limestone, chunks of plaster, and three types of nails. The sizes and types of nails indicated that the courthouse interior was nicely finished with wooden mantel pieces, base boards, window trim and door frames. Several examples of a specially shaped brick, called a water table brick were found during the 2004 excavations. The water table is a molding or other projection in the exterior wall of a building intended to direct water away from the foundation to prolong its use. A course of these bricks might be placed around the perimeter of the foundation of a building, or at the base of window surrounds to serve the same purpose, that is, to direct rain water away from the foundation.

The volume of brick debris, massive limestone foundation, and the small quantity of nails found in archeological excavations at the courthouse indicate that it was a two-story brick building. The materials necessary to construct it (except for window panes) would have been fairly readily available. Suitable timber was present in great abundance. Limestone is abundant throughout the area. The General Land Office surveyors and other nineteenth century travelers to the area identified several different species of oak and hickory along with yellow pine and cypress. Cypress probably would have been the preferred species for beams and structural members since it cuts well, is resistant to rot, and would have been easier to move. The 1830s Ficklin-Imboden house in nearby Powhatan was built of cypress. Ash and elm are good woods for fashioning tool handles that were also surely used by the courthouse builders. Ash burns well and could have been used in the brick-making process. The bricks and mortar were undoubtedly made on site. The only raw materials required were clay, sand, and water. Only three ingredients, lime, sand, and water were needed to create mortar.

The volume of brick debris, massive limestone foundation, and the small quantity of nails found in archeological excavations at the courthouse indicate that it was a two-story brick building. The materials necessary to construct it (except for window panes) would have been fairly readily available. Suitable timber was present in great abundance. Limestone is abundant throughout the area. The General Land Office surveyors and other nineteenth century travelers to the area identified several different species of oak and hickory along with yellow pine and cypress. Cypress probably would have been the preferred species for beams and structural members since it cuts well, is resistant to rot, and would have been easier to move. The 1830s Ficklin-Imboden house in nearby Powhatan was built of cypress. Ash and elm are good woods for fashioning tool handles that were also surely used by the courthouse builders. Ash burns well and could have been used in the brick-making process. The bricks and mortar were undoubtedly made on site. The only raw materials required were clay, sand, and water. Only three ingredients, lime, sand, and water were needed to create mortar.

3D Reconstruction of the Courthouse

Along with taking into consideration the archeological evidence from the courthouse excavations (e.g., size of the building, width of foundation, construction materials) and information from contemporaneous courthouses in the region (interiors and exteriors), a series of decisions were made about specific design elements of the 3D reconstruction. Some of the design features have a long history, back to the earliest colonial settlements in Virginia. Others may have been chosen by the commissioners of the courthouse or perhaps even the builder. These include: the size and shape of windows, the number of chimneys and fireplaces, the pattern used in bricklaying, the presence or absence of porches (and materials), hardware, outer doors, and interior layout of rooms. The cost of construction undoubtedly entered into design and construction decisions.

We enlisted the assistance of former architect Steve Saunders in visualizing what the Davidsonville courthouse may have looked like. Steve is currently an interpreter at Powhatan State Park. We provided him with photographs and drawings from our archeological excavations, and details of artifacts we found (window glass, types of nails, bricks, mortar, plaster, etc.). Steve created what he calls an “artist’s reconstruction” of the courthouse, inside and out.

He suggested that the building would have had a gable roof rather than a hip roof. A gable roof is simpler and more stable for a rectangular structure. The “double bricks” and foundation remnants found in our excavations told Steve that the first floor of the courthouse was “on grade” rather than having a wooden floor and crawl space. The most difficult course for the mason would have been the first or “starter” course because it made the transition from less regular foundation stones (of limestone) to a very level brick course. That transition would have occurred in the somewhat irregular mortar joint between the two.

Details in our “first draft” of the courthouse exterior such as arched brickwork and windows, and stack bond (decorative bricklaying technique) along window edges would have required special skills to create, and would probably have been expensive, so we took them out. Stone lintels at the tops of the windows were proposed and added. We added a soldier course of brick on the outside of the building to mirror the second floor location. A soldier course is a row of bricks standing on end with the narrow edge facing out.

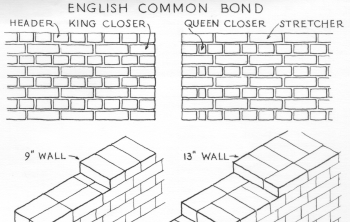

Steve recommended that bricks in the courthouse walls would have been three or four brick layers (wythes) thick in an interlocked bond pattern. The simplest bond is the common bond where every sixth brick course is a header. A header is a brick laid with its short side exposed. We used the Flemish bond in the 3D reconstruction, since it is more decorative.

Steve recommended that bricks in the courthouse walls would have been three or four brick layers (wythes) thick in an interlocked bond pattern. The simplest bond is the common bond where every sixth brick course is a header. A header is a brick laid with its short side exposed. We used the Flemish bond in the 3D reconstruction, since it is more decorative.

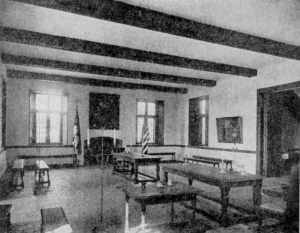

The courtroom in the 1676 Old Statehouse at St. Mary’s City, Maryland was a starting point in recreating the Davidsonville court room. We discovered that the basic size and layout of court rooms in America did not change for hundreds of years. In fact, architectural historian Carl Lounsbury (1989:222) observes that “The arrangement of the courtroom itself from the 1730s through the early nineteenth century…showed little variation.” Photographs of court rooms in the restored Jacob Wolf House (which served as the seat of justice for Izard County from 1825-1835) and the Confederate State Capitol at Washington, Arkansas (at Historic Washington State Park), along with a written description of the proposed Randolph County courtroom (built in 1839) also aided the courtroom reconstruction.

The courtroom in the 1676 Old Statehouse at St. Mary’s City, Maryland was a starting point in recreating the Davidsonville court room. We discovered that the basic size and layout of court rooms in America did not change for hundreds of years. In fact, architectural historian Carl Lounsbury (1989:222) observes that “The arrangement of the courtroom itself from the 1730s through the early nineteenth century…showed little variation.” Photographs of court rooms in the restored Jacob Wolf House (which served as the seat of justice for Izard County from 1825-1835) and the Confederate State Capitol at Washington, Arkansas (at Historic Washington State Park), along with a written description of the proposed Randolph County courtroom (built in 1839) also aided the courtroom reconstruction.

One tricky element was the placement and configuration of the staircase to the second floor of the courthouse. We struggled with this, but eventually incorporated the interior staircase configuration of the restored Randolph County courthouse (in Pocahontas, Arkansas).

A clerk’s office and a jury deliberation room were included on the first floor of the reconstruction. The clerk was one of the most important people in county government in the early nineteenth century. At this time many people were unable to read or write. Even those who knew how to read used phonetic spellings in letters or other documents. The county clerk made clear, readable records of all court hearings and other documents and forms necessary for the county to operate. The room designated as the jury deliberation room could have served other uses when court was not in session.

References Cited

Allen, Desmond W.

- 1995 Early Lawrence County, Arkansas, Records, 1817-1830. Arkansas Research, Conway, Arkansas.

Cande, Kathleen H.

- 2005 Davidsonville: The Search For Arkansas’ Oldest County Seat Town, Randolph County, Arkansas. Final Report, Project 04-07. Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayetteville. Submitted to the Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism, Little Rock.

- 2006 Expanding Public Interpretation at Old Davidsonville State Park. Year 1 Report, Project 05-01. Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayetteville. ANCRC Project 05-006. Submitted to the Arkansas Natural and Cultural Resources Council, Little Rock.

Cande, Kathleen H., Jared S. Pebworth, Michael M. Evans, and Aden Jenkins

- 2008 Muffins, Chimneys and Clinkers: Expanding Public Interpretation at Old Davidsonville State Park, Randolph County, Arkansas. Year 3 Report, Project 07-01. Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayetteville. ANCRC Project 07-007. Submitted to the Arkansas Natural and Cultural Resources Council, Little Rock.

- 2009 Archeological Excavations in Lots 9, 19, 21, and the Public Square at Davidsonville Historic State Park, Randolph County, Arkansas. Year 4 Report, Project 09-02. Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayetteville. ANCRC Project 09-006. Submitted to the Arkansas Natural and Cultural Resources Council, Little Rock.

Cande, Kathleen H., Jared S. Pebworth, Aden Jenkins and Michael M. Evans

- 2007 “A Public House of Entertainment”: Expanding Public Interpretation at Old Davidsonville State Park, Randolph County, Arkansas. Year 2 Report, Project 06-01. Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayetteville. ANCRC Project 06-005. Submitted to the Arkansas Natural and Cultural Resources Council, Little Rock.